White Abalone

Haliotis sorenseni

White Abalone

Haliotis sorenseni

Morphology

White abalone have oval-shaped domed shells and a strong muscular “foot” that allows them to hold tightly to rocks and other hard surfaces. The shells have 3 to 5 respiratory pores that can be easily seen because they are elevated above the shell’s surface. The shells, which can reach up to 25 centimeters in length, are commonly covered with other organisms.

Habitat and Range

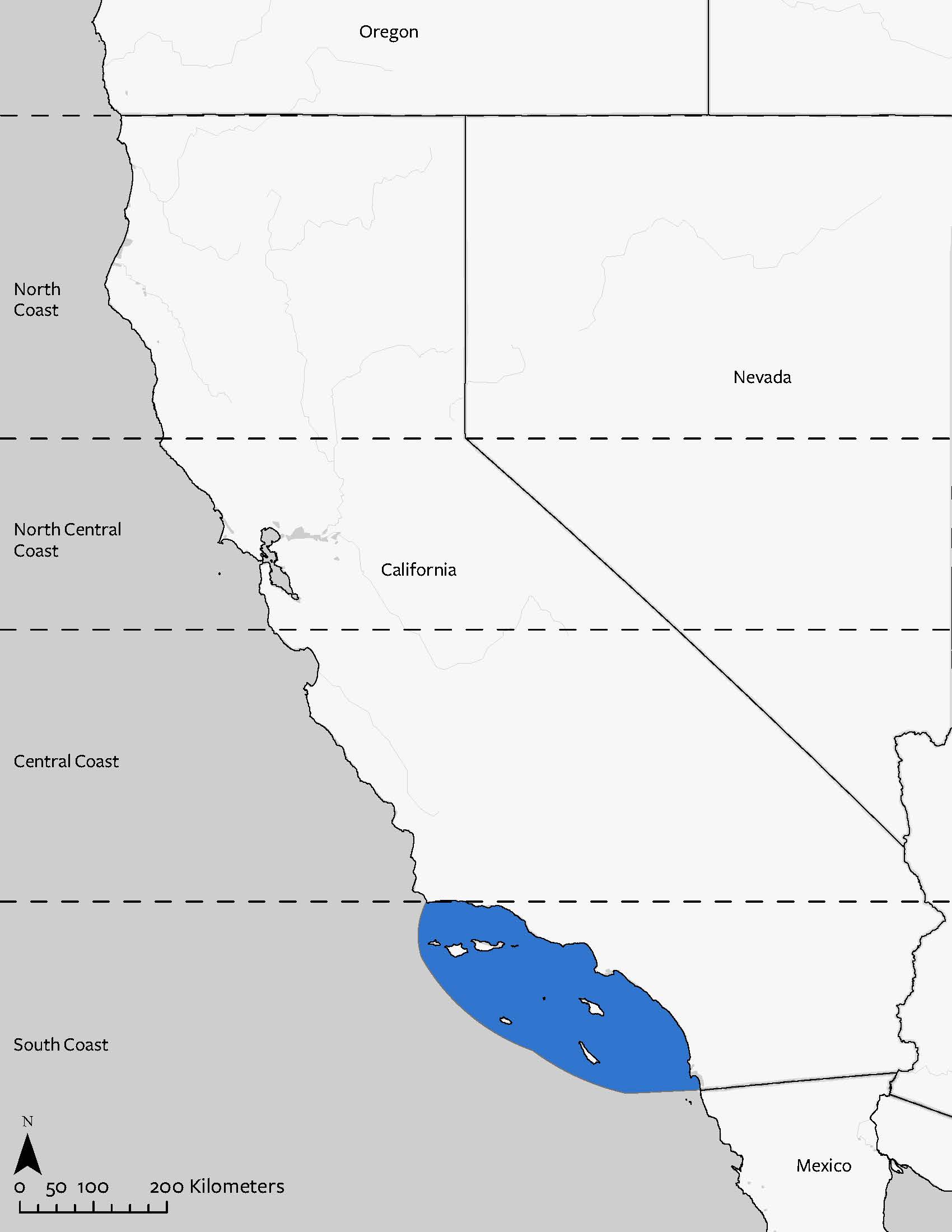

White abalone inhabit rocky substrates at depths as shallow as 6 meters, but typically occur at depths of 15 to 55 meters, making them the deepest living abalone species. Their range in coastal waters extends from Point Conception, California to Punta Abreojos, Baja California, Mexico.

Range Map

Reproductive Biology and Life History

White abalone have two sexes (male and female) and reproduce via broadcast spawning, whereby adults release millions of eggs or sperm into the water column. Because eggs and sperm must meet in the water for fertilization, males and females have to be within a few meters of each other for fertilization to have a good chance of succeeding. Fertilized eggs develop into larvae that remain in the water column for 1 to 2 weeks, after which larvae settle on suitable substrates, triggered by chemical, physical, and biological cues. Settled larvae transform into juvenile abalone within one to two months depending on local conditions. They do not reach reproductive maturity until they are 4 to 6 years old, with a total lifespan of 35 to 40 years.

Ecology

White abalone graze on kelp and algae and in the process create open spaces on rocks for a multitude of other species. This has inspired the label “ecosystem architects” for the species. When grazing they use their radula (a tongue-like organ) to scrape algae off rocks and can catch floating food with their foot. As juveniles they are vulnerable to predation and hide in crevasses, under rocks or even amongst the spines of sea urchins. As larvae, planktonic larvae may disperse as much as 50 meters from parents; but once the larvae have settled and metamorphosed into juveniles their mobility is limited.

Culture and Historical Context

White abalone has the distinction of being the first marine invertebrate to be listed as endangered under the U.S. Endangered Species Act. This happened in 2001, and the species has remained on the endangered list for more than two decades.

Archeological records indicate Native Americans harvested a variety of abalone species at least 12,000 years ago. In California, abalone protein was an important component of coastal tribes’ diets. Shallow water red and black abalone, had been sustainably harvested for thousands of years until commercial fisheries expanded in the late 1800s and early 1900s. Being ‘easy pickings’ in the intertidal zone, red and black abalone were quickly decimated. Then, commercial harvest moved to deeper waters, targeting pink and green abalone, which inhabit slightly deeper waters. Finally, white abalone, being the deepest-dwelling species, were the last to be heavily exploited.

Date modified: January 2025

This animal can be found at the Aquarium of the Pacific

Primary ThreatsPrimary Threats Conditions

Threats and Conservation Status

Over-exploitation was the primary factor underlying the near disappearance of white abalone in the 1970s and 1980s. More recently the major threat to white abalone is the disease called withering syndrome (WS).

Since the species has been listed under the Endangered Species Act numbers have remained low. Abalone are so scarce that they cannot be sampled by laying out transects or quadrants. Instead, scuba divers or remotely operated vehicles (ROVs) are used to survey for them in deeper waters. We report ROV data on white abalone from a sea mount site in the South Coast region, about 130 kilometers west of San Diego. Instead of simply recording abalone per dive, the ROV data can be scaled by the length of the dive to adjust for uneven search efforts. As can be seen from this very limited time series, abalone is clearly remaining very scarce and may even still be declining (noting that the asterisk in the graph is a zero).

Although harvest of white abalone was banned in 1997, the species has been slow to recover due to two features of its biology. First, in the wild reproduction has not been reported until they are 4 years old, although in captivity, gonads develop at 2 to 3 years old. Second, male and female adults must be close enough together that the sperm have a good chance of finding an egg to fertilize. Given the absence of natural recovery in the wild, conservation efforts for white abalone have focused on captive breeding and then outplanting of mass produced juvenile abalone into the wild, once they have reached a size of approximately 2.5 centimeters.

The Aquarium of the Pacific is part of a coalition of 40 partner institutions working to contribute to white abalone recovery. The first release of captively-bred abalone was of about 800 juveniles in 2019 using two different styles of semi-protected cages to acclimate the young abalone. Since then there have been releases almost every year for a total of over 14,000 as of 2024. That might seem like a large number, but the goal established by NOAA in it’s 2008 Final White Abalone Recovery Plan entailed scaling up aquaculture production of white abalone to levels that could support releasing 10,000 to 25,000 every year (as opposed to 14,000 over five years). There is now a major effort to achieve this scaled up production, an effort in which the Aquarium of the Pacific is taking part.

The disease “withering syndrome” impacts all California abalone, including the white abalone. There is evidence that the stress of ocean warming and acidification may reduce abalone resistance to the disease. As is the case with all restoration (or outplanting) programs — returning a species to the point of recovery is complicated. While the historical record indicates Southern California has been ideal habitat for white abalone, recent modeling studies suggest that sites north of Point Conception may offer a thermal refuge as climate change continues to drive sea surface temperatures up in areas to the south.

Population Plots

Data Source: NOAA ROV surveys.