Sunflower Sea Star

Pycnopodia helianthoides

Sunflower Sea Star

Pycnopodia helianthoides

Morphology

The sunflower sea star is the world’s largest sea star species, with an arm-to-arm span that can reach a meter. They start with five arms and then add arms as they develop, ultimately ending up with as many as 24 arms radiating from a central disk. When fully grown, they can weigh up to 5 kilograms. Their colors can be purple, orange, blue, brown, yellow and combinations of all! Their 15,000 tube feet and flexible skeleton gives them surprising mobility. Their stomach and mouth, which is on their underside, can open wide and expand to consume large prey.

Habitat and Range

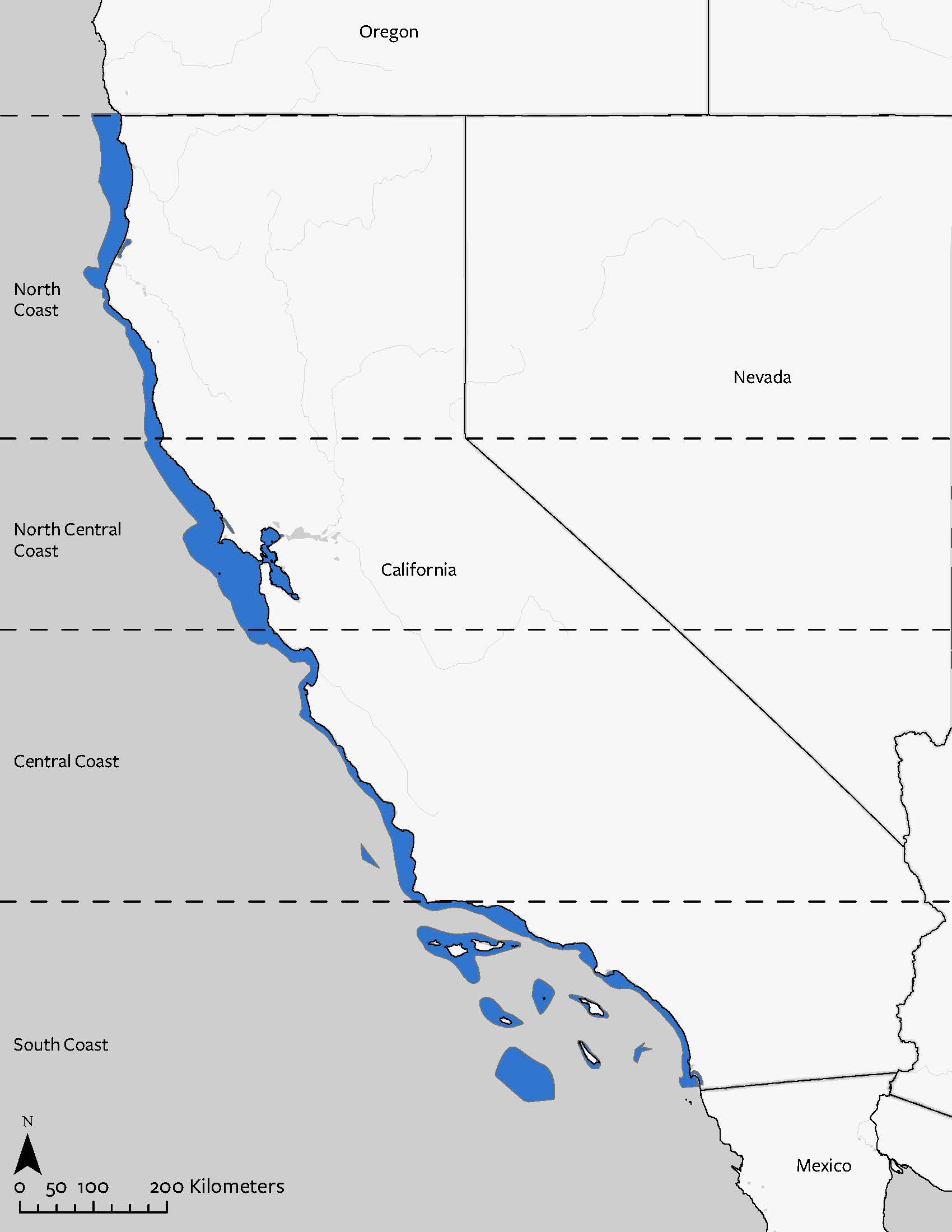

Sunflower sea stars are found along the eastern Pacific coast from the Aleutian Islands, Alaska to Baja, Mexico. They inhabit rocky intertidal, kelp forests, and even sand/mud flats. They range in depth from the intertidal to 400 meters, though they are most commonly found at depths ranging between zero and 30 meters.

Range Map

Reproductive Biology and Life History

Sunflower sea stars have separate sexes and reproduce sexually through broadcast spawning. During the spawning process these sea stars use their arms to arch up and raise their body, to facilitate more efficient release of eggs and sperm into the water column. Fertilization happens by chance in the water column and larvae live as plankton for 4 to 10 weeks before settling on the ocean floor and metamorphosing into tiny sea stars. Their larvae are planktotrophic, meaning they feed on plankton while floating in the water column. They can float in ocean currents far and wide while they wait for cues to settle. Sunflower seastars reach reproductive maturity as early as three years of age, although this likely depends on their size. We do not know how long they live in the wild as there is no way to age them. Individuals have lived in aquaria for decades.

Ecology

Sunflower sea stars are voracious generalist predators feeding primarily on abundant invertebrates in the area, including sea urchins, mussels, clams, sea cucumbers, and other invertebrates. They will also consume dead prey, including fish carcasses. They are among the fastest moving sea stars – reaching speeds of 1 meter per minute. They use their strong sense of smell and light receptors at the tip of each arm to locate their prey. Like other sea stars, they can regenerate damaged or missing arms and even clone themselves if a detached arm has a portion of their central disc.

Culture and Historical Context

Sunflower sea stars play a key role in kelp ecosystems due to their ability to hold urchin populations in check. Following the sea star’s population collapse that resulted from a sea star wasting syndrome (SSWS) epidemic, researchers documented what is called a trophic cascade: decline in sunflower sea stars yielded increases in urchins, which in turn caused declines in kelp due to overgrazing by urchins. This cascade was detected within less than a year of the wasting disease’s epidemic of 2013. Several long term monitoring programs have been key to tracking the collapse of sunflower sea stars including California’s MPA monitoring network and a global community science effort (called REEF https://www.reef.org/what-reef), which relies heavily on volunteer divers to collect subtidal data. It was data from REEF that led to quick peer reviewed publications shortly after the disease emerged. Because REEF had collected “before” (2010) and “after” (2014) data it was possible to document the trophic cascade that ensued. REEF, MARINe, the MPA monitoring network and other long term monitoring sites will provide essential information on the impact and recovery of sunflower sea stars. There is a MARINe Sea Star Wasting Syndrome Observation Reporting website (seastarwasting.org) to support community science contributions to the sunflower sea star story.

Date modified: January 2025

This animal can be found at the Aquarium of the Pacific

Primary ThreatsPrimary Threats Conditions

Threats and Conservation Status

Sunflower sea stars are listed as critically endangered by the IUCN and have been proposed for listing under the US Endangered Species Act. The primary cause of the strong decline in abundance evident in the data shown here is the sea star wasting disease that decimated sea star populations, causing greater than a 95% global decline between 2013 and 2018. Combining data from the south coast and north coast, trend analysis reveals an average annual decline of 3.6%. However, the decline was not gradual and is not well-described by a linear trend line. Graphing abundance data by region it is clear the decline was precipitous everywhere.

Subsequent to the population collapse, recovery in the wild has been slow or non-existent thus far. For example, resampling over 80 sites in 2019, 2020, and 2021, no sunflower sea stars were detected. It may be that ocean warming has exacerbated the sunflower sea star collapse. The wasting disease outbreak coincided with anomalous ocean heat waves. Laboratory experiments with other sea star species have documented a strong effect of water temperature on the wasting disease trajectory, but such lab experiments are lacking for sunflower sea stars and will not be forthcoming due to the extraordinary rarity of the species.

Because of the slow recovery and the sunflower sea stars’ important role in kelp ecosystems, major efforts are underway to captively breed this species. The captive breeding efforts are a way to ensure that a robust population is held in captivity as a safeguard against extinction.

Friday Harbor Labs was the first lab to unlock the possibility of a sunflower sea star captive breeding program in partnership with The Nature Conservancy. As of 2025, eight institutions in California house juvenile sunflower sea stars. Before recent efforts, no scientists had ever attempted to breed wild-caught sunflower sea stars in captivity. Protocols are still under development with the special challenge of keeping the disease out of facilities, minimizing cannibalism among young sea stars, sperm storage and scaling up production. To meet these challenges, The Nature Conservancy has launched the Pycnopodia Recovery Working Group, a coalition of partners to meet the widespread decline of sunflower sea stars — which extends from Alaska to Baja. The Aquarium of Pacific, along with several other aquaria that have sunflower sea stars in their care, is participating in a network of Aquaria working together to improve techniques for mass rearing of these highly endangered sea stars.

Population Plots

Data Source: The data were obtained from the California MPA monitoring program. The numbers at the top of each bar represent the number of sites surveyed. Asterisks on a graph signify a zero (as opposed to missing data or no data).