Giant Sea Bass

Stereolepis gigas

Giant Sea Bass

Stereolepis gigas

Morphology

Giant sea bass earn their name with a maximum verified weight of 253 kilograms and maximum reported length of 2.3 meters. They are distinguished by a single, strongly notched dorsal fin that fits into a groove on their back and a notably large head and mouth. They have small teeth that are located in the back of their mouth.

The coloration of giant sea bass changes throughout their lifespan. Juveniles are bright red or orange with dark spots, whereas adults tend to be grayish-black or dark brown, with a lighter belly and distinctive dark spots on their sides. Adults have the ability to change their color, albeit not as dramatically or rapidly as an octopus or chameleon. This ability is thought to be used for communication, although the meaning of specific color changes is unknown.

Habitat and Range

Giant sea bass reside in nearshore kelp forests and rocky reefs from Humboldt Bay to Oaxaca, Southern Mexico, and into the Gulf of California. Their population is concentrated southward from Point Conception to the southern tip of Baja California. They are commonly seen in artificial reefs and shipwrecks as well as natural habitats. Juveniles favor shallow, nearshore waters along sandy beaches near the heads of submarine canyons.

Range Map

Reproductive Biology and Life History

Giant sea bass can live to at least 76 years old and reach sexual maturity between 11-13 years old. Spawning has rarely been observed in nature, but they are known to be broadcast spawners, aggregating in specific locations during the summer months to release sperm and eggs into the water column. They spawn multiple times with multiple mates over the course of a summer spawning season. During this time, a female may produce as many as 60,000,000 eggs.

Ecology

As a top predator, giant sea bass have a diverse diet that includes stingrays, skates, small sharks, lobster, octopus, squid, and numerous smaller fish. They are ambush predators, using their large mouths to create a vacuum that sucks in prey. Although they generally move slowly they are capable of short bursts of speed as an escape mechanism.

Known as gentle giants, giant sea bass are harmless to humans and are often seen swimming up to divers, following them around during their dive. Some individuals have been recorded traveling over 150 kilometers, whereas others inhabit the same kelp forest year-round. One of the most unusual adaptations in giant sea bass is their ability to produce a distinctive “boom” sound, which has been described as similar to a concert bass drum. The sound is generated by the fish squeezing its ribs with special muscles onto the swim bladder.

Cultural and Historical Context

Giant sea bass were once commonly found in fish markets throughout Southern California, where they were a prized catch for commercial and recreational fishers. The commercial catch of giant sea bass peaked in 1932 and the recreational catch in California peaked in 1963. Even though their numbers had already declined significantly, giant sea bass were still valued as “big game” trophies for California spearfishers well into the 1970’s. However, overfishing and fishing regulations have changed all that. Currently it is prohibited to take or harvest giant sea bass in California state waters. Any giant sea bass incidentally caught during other fishing activities must be returned to the water. There is a limited exception for commercial gill net and trammel net fisheries, which are allowed to keep one incidentally caught fish per trip.

In recent years, giant sea bass have become valuable for ecotourism, particularly in the scuba diving industry. Encounters with these fish are considered highlights for divers, comparable to wolf or bison sightings in Yellowstone National Park. The average non-consumptive annual value of these iconic “giants” to the diving community is estimated at over $2.3 million.

Date modified: January 2025

This animal can be found at the Aquarium of the Pacific

Primary ThreatsPrimary Threats Conditions

Threats and Conservation Status

In 1996, the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) listed giant sea bass as Critically Endangered, citing a fragmented population and a continuing decline in mature individuals. The cause of the decline was no surprise: overfishing.

With their large size, giant sea bass had been favored targets for fishers since the late 1800s. By the end of the 20th Century, the giant sea bass population became so depleted by over-exploitation that California implemented a fishing ban in 1981 (with a few special exceptions or “allowances”). The exceptions allowed commercial fishing boats to retain up to two giant sea bass caught as bycatch while targeting California halibut or white sea bass with set gillnets. Numbers continued to decline, and in 1988, this allowance was reduced to one incidentally caught giant sea bass. Other measures have also been put in place to protect these magnificent fish and there is some indication they are making a slow recovery.

In particular, taking advantage of the distinctive spot patterns found on adult fish and repeat sightings by divers, biologists have estimated a population size of ~1200 adult fish for giant sea bass in Southern California. These “mark-resightings” data have also been analyzed to produce annual population growth (or decline) rates as shown below:

| Year | Annual Population Rate of Change |

|---|---|

| 2016 | 1.05 |

| 2017 | 1.42 |

| 2018 | 1.17 |

| 2019 | 1.59 |

| 2020 | 1.04 |

| 2021 | 0.79 |

| 2022 | 0.99 |

Those seven years yielded an estimated average annual growth rate of 1.08 or 8%. This leaves open the question of a longer-term trend.

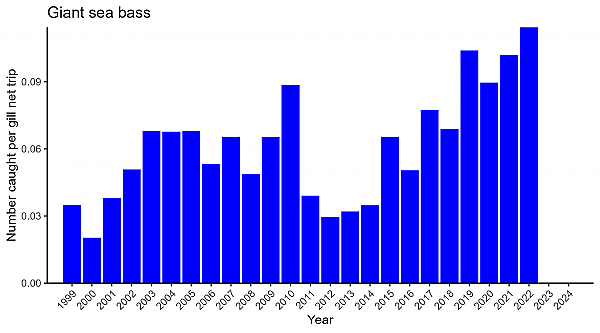

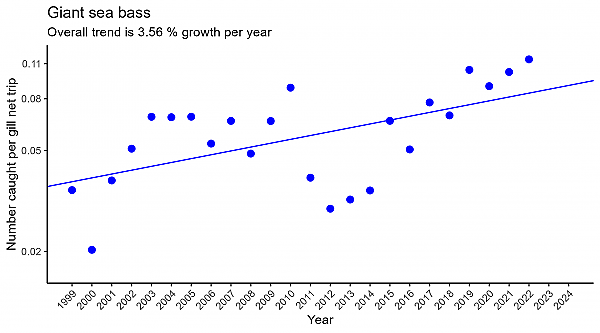

California Department of Fish and Wildlife consistently reports annual data on the number of giant sea bass incidentally caught per gill net set. Plotting these CDFW incidental take data over the time period 1999 to 2022, indicates that abundance is increasing. Applying a more formal regression analysis reveals an average 3.56% increase per year over that twenty-four year time period. Thus both detailed population modeling and cruder long-term fisheries data suggest a slow recovery of giant sea bass.

Unfortunately, it’s still not uncommon to encounter giant sea bass with large fishing hooks in their mouths or even spears embedded in them. Plastic pollution also poses a threat, with giant sea bass reported with plastic rings stuck around their necks (“choked to death” being the ultimate outcome). In addition, an average of 126 giant sea bass are still caught in gill nets as bycatch and sold in California each year. Lastly, climate change is a big unknown. Giant sea bass have been so rare over the last thirty years that we lack information on the possible impacts of ocean warming, but should be alert to possible further stress.

Overall, giant sea bass is an authentic, ongoing conservation success story. Once driven to the brink of extinction due to over-exploitation, the species has shown signs of a slow recovery following the implementation of regulations and protective laws. However, emerging challenges like climate change and pollution highlight the critical need for ongoing monitoring and research to secure the species’ future.

Population Plots