California Spiny Lobster

Panulirus interruptus

California Spiny Lobster

Panulirus interruptus

Morphology

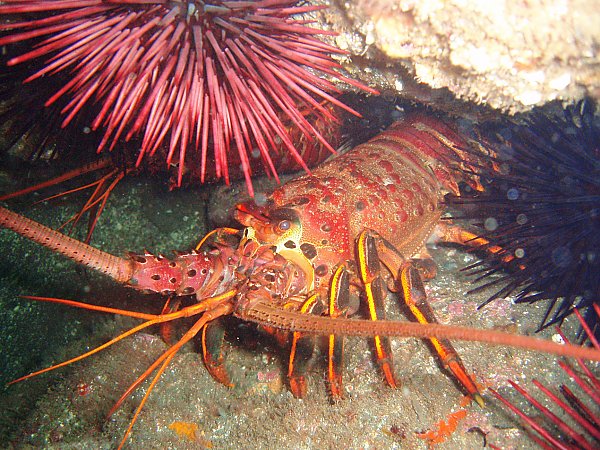

California spiny lobsters can grow up to 60 centimeters in total length, with males sometimes reaching weights of up to 7.4 kilograms. They have a reddish-brown exoskeleton with spiny projections on the carapace and abdomen. Unlike Maine lobsters, they lack large claws and instead have five pairs of walking legs. Their long antennae are used for sensory perception and communication, as they play their antennae like a violin.

Habitat and Range

California spiny lobsters are found along the Pacific coast of North America, ranging from Monterey Bay, California to Baja California, Mexico. They are rarely seen north of Point Conception due to colder water temperatures. These lobsters prefer rocky reef habitats and are often found in kelp forests and surfgrass beds at depths up to 65 meters.

Range Map

Reproductive Biology and Life History

Spiny lobsters reach sexual maturity between 4 and 6 years of age. Their reproductive cycle is complex, taking approximately two years from mating to the settlement of larvae. Females carry fertilized eggs on their abdomen until they hatch, using specialized appendages to groom and maintain the egg mass. After hatching, the larvae go through several planktonic stages before settling into their benthic adult form. In the wild, California spiny lobsters can live between 11 and 30 years, although most do not survive much beyond 7 to 10 years due to fishing pressures, noting that in California, spiny lobsters typically reach legal size for harvest between the ages of 8 and 13. In captivity, they have been known to live up to 25 years.

Ecology

Spiny lobsters feed on invertebrates such as mussels in rocky habitats, and urchins in kelp forest habitats. Along with sea stars and sea otters, spiny lobsters play an important role in maintaining balance in California kelp forests by serving as predators of urchins. They have also been known to be scavengers that feed on algae and dead animals. California Spiny Lobsters are nocturnal and semi-social. They hide in crevices during the day and emerge at night to forage, traveling up to 600 meters in search of food. Spiny lobsters undertake seasonal migrations, often in large single-file lines, which may be related to finding more favorable temperatures or food sources. If threatened while foraging, spiny lobsters can quickly flick their tails to propel themselves backwards from predators such as giant sea bass and larger sheephead.

Cultural and Historical Context

In the late 1800s, spiny lobsters were so plentiful in Southern California waters that a single person could catch 500 pounds in just two hours. A commercial fishery for spiny lobsters in Southern California was initiated in the late 1800s. Overfishing ensued, and due to declining populations, the fishery was closed for two years in 1909 and 1910. When it reopened in 1911, lobsters were once again abundant. Currently, the California spiny lobster is the third-most economically valuable fishery in California behind Dungeness crab and Market Squid, with an annual economic value of $14M for commercial harvest and another $30M value as a recreational fishery.

Date modified: January 2025

This animal can be found at the Aquarium of the Pacific

Primary ThreatsPrimary Threats Conditions

Threats and Conservation Status

The stock of California spiny lobster is considered well-managed, with no evidence of overfishing. The key components of this lobster’s management are monitoring of commercial catch, catch per unit effort, and the number of eggs produced by population. Using these data, the state establishes minimum legal-size limits, seasonal closures, and gear restrictions to prevent overfishing. For recreational fishing, the bag limit is seven lobsters per person, and the minimum legal size is 3¼ inches in carapace length. In recent years, surveys have revealed an annual increase of greater than 10% a year, a strong increase. The increase in spiny lobster density in recent years is likely due in part to the establishment of the California MPA network beginning in 2003 with the Channel Islands, as well as the 2016 management plan. The impact of MPA’s is evident by comparing rates of increase inside and outside MPA’s in Southern California. In addition, studies have shown that lobsters tend to be larger inside MPA’s compared to outside MPA’s and an increased size in lobsters can translate to higher reproductive output. Overall, spiny lobster is classified as a strong increasing.

Population Plots

Data Source: Monitoring and Evaluation of Kelp Forest Ecosystems in the MLPA Marine Protected Area Network. California Ocean Protection Council Data Repository. doi:10.25494/P6/MLPA_kelpforest.7. Mark H Carr, Jennifer E Caselle, Brian N Tissot, Daniel J Pondella, Daniel P Malone, Kathryn D Koehn, Jeremy T Claisse, Jonathan P Williams, Avrey Parsons-Field, & Sean F Craig. (2024).