Bull Kelp

Nereocystis luetkeana

Bull Kelp

Nereocystis luetkeana

Morphology

Bull kelp is a large subtidal algae that grows in “forests” or “stands” that reach the surface, forming a canopy. Each individual has a small holdfast that anchors it to rocks and a long stipe with a single, buoyant bulb that pulls it toward the surface. The bulb bears long flat blades that stream in the current. Individuals, including the blades, can be 30 meters long.

Habitat and Range

Bull kelp is a cold water species, found from the Eastern Aleutian Islands, Alaska, to San Luis Obispo County, California. It is most common north of San Francisco, where it provides structure for a rich community of understory seaweeds, invertebrates and fish. Bull kelp thrives in nearshore habitats with strong currents that bring cold, nutrient rich waters to the surface.

Range Map

Reproductive Biology and Life History

Bull kelp is an annual alga that grows from embryo to adult in a single year, though some individuals may persist into the following growing season. When the kelp is mature, dark patches made up of millions of spores form on the blades. These patches are released and fall to the bottom, and the spores swim out, powered by two flagella. Spores settle and develop into a microscopic cluster of filaments. These filaments produce eggs or sperm. Fertilized eggs grow into the huge bull kelp, and the cycle continues.

Ecology

NOAA has designated bull kelp as a Habitat Area of Particular Concern for Pacific Coast groundfish. Bull kelp forests support rich biodiversity beyond just groundfish by offering food, shelter, and nursery areas for numerous species. Bull kelp canopies have been shown to mitigate ocean acidification stress through their uptake of carbon dioxide for photosynthesis. This can create temporary and local refugia for other organisms. Bull kelp grows at rates of up to 25 centimeters per day, which translates into a carbon capture rate comparable to terrestrial forests. Even kelp detritus is important as it delivers nutrients and food to other ecosystems such as beaches and deepwater canyons.

Cultural Significance and Historical Context

Bull kelp was used extensively in native cultures for fishing, hunting, food preparation and storage, as well as to create fishing and harpoon lines. Bull kelp was also used in households to fashion storage containers or water conduits. Archeologists have proposed a “kelp highway hypothesis”, which suggests that kelp ecosystems were key to the migration of humans from Asia to the Americas, and down the coast of Western North America to California. The idea here is that the tremendous productivity of these nearshore coastal ecosystems provided food and resources to the early arrivals to North America.

Date modified: January 2025

This algae can be found at the Aquarium of the Pacific

Primary ThreatsPrimary Threats Conditions

Threats and Conservation Status

The greatest threats to bull kelp are grazers that consume kelp directly, especially sea urchins, and warming ocean temperatures. In Northern California, a series of events occurred in 2014 to 2015 with devastating results. The sunflower star, an urchin predator, died off (possibly from a virus), allowing its urchin prey to increase dramatically. These large herbivorous urchin populations then overgrazed bull kelp forests, creating extensive barrens. At the same time, a warm ocean water event occurred that impacted the growth of kelp, which requires cold, nutrient-rich water to grow. Together, this double-whammy of stressors caused more than a 90% reduction in bull kelp populations along the coast of Northern California. Because some populations survived, experimental restoration efforts that include transplantation of adults or juveniles, plus the removal of urchins, are underway, with varying success. Dredging and shoreline development can also impact populations.

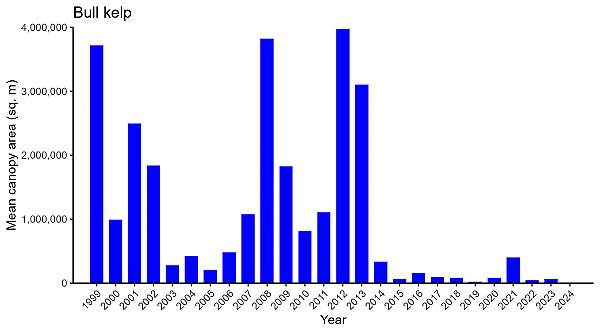

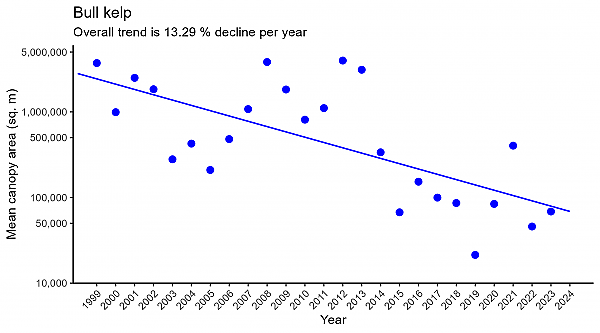

Abundance of kelp on large scales is typically measured by aerial surveys and remote sensing of canopy area via satellites. Unfortunately, current satellite-based remote sensing does not allow one to distinguish between giant kelp and bull kelp, but this may be possible in the near future. In the meantime, close observations allow biologists to distinguish the species from field or high-resolution aerial surveys; giant kelp is the dominant canopy-forming kelp south of the Big Sur coast, but overlaps extensively with bull kelp into the Monterey Bay. The data thus represent the kelp canopy area detected by remote sensing from San Francisco Bay to the California/Oregon border.

The two striking features from this data are the collapse of the bull kelp canopy in 2014, particularly around Northern California, and the extraordinary variation in populations from year to year. The 13% annual decline since 1999 explains 45% of the variation from 1999 onward, and resulted in the species receiving a strong decline trend.

Population Plots

Data Source: kelpwatch.org