Black Abalone

Haliotis cracherodii

Black Abalone

Haliotis cracherodii

Morphology

Black abalone are large marine snails with one dark blue to black oval-shaped shell up to 20 centimeters in length. The shell has five to nine respiratory pores flush to the surface used to breathe, remove waste, and reproduce. The shell interior is pearly, with green and pink iridescence. They use a fleshy muscular “foot” to move and to cling tightly to rocks.

Habitat and Range

Historically, black abalone could be found from Del Norte County, California to Southern Baja California. Their current range, based on recent consistent population observations, is from Point Arena, California to Bahia Tortugas, Mexico. They live on rocky substrates from the mid intertidal zone to depths of around six meters but are most readily observed in the mid-low intertidal, typically on complex surfaces and deep crevices that provide shelter.

Range Map

Reproductive Biology and Life History

Black abalone are broadcast spawners, with males releasing sperm and females releasing eggs into the water column in a synchronized fashion. The synchronization is achieved because the two sexes are triggered to release their gametes by identical environmental cues. Older and larger individuals produce significantly higher numbers of gametes than newly mature, smaller individuals. Reproductive success is dependent on proximity to potential mates – ideally with less than a few meters between individuals. If fertilized, the resulting embryos have a short planktonic larval stage of about three to ten days in the water column before settling. Because the larval stage is short, dispersal is thought to be limited, which has implications for recovery of the species. Adult abalone reach sexual maturity when shell length is about five centimeters for females and nearly four centimeters for males. Black abalone are estimated to have a lifespan of ~30 years.

Ecology

As slow-moving bottom-dwellers, adult black abalone rely on drifting algae in the intertidal as a food source. They feed primarily on giant kelp and feather boa kelp in Southern California (south of Point Conception) and bull kelp in Central and Northern California, although other algal species are consumed as well. Juveniles tend to be more mobile and may graze on microflora, such as diatom films.

Cultural Significance and Historical Context

Black abalone shells were traded extensively among Native American groups. Shells were used for decorations and to create jewelry. Trade routes for these shells originated in southern California and extended eastward, reaching beyond the Mississippi River. This widespread trade network highlights the importance of black abalone among various Indigenous communities both as meat for food, and shells for their beauty and trading. For many California coastal tribes, abalone held deep spiritual meanings that were passed down through generations via ceremonies, songs, and stories. Chumash and Yokut incorporated abalone shells into burial rituals. The Chumash also used abalone shells to waterproof their plank canoes.

Date modified: January 2025

Primary ThreatsPrimary Threats Conditions

Threats and Conservation Status

Black abalone were once so abundant along the California coast that they were a major food source for Indigenous peoples of California’s coast – with 10,000 years of sustainable harvest. More recently commercial fisheries arose for black abalone in the 1850s and later in the 1950s. The commercial harvest peaked in 1973 at 868 metric tons. After that peak harvest, a combination of overharvest and a fatal disease called withering syndrome (WS) caused severe population declines and ultimately the closure of the fishery in 1993. WS is caused by a gastrointestinal pathogen that disrupts digestion and causes starvation, leading to foot atrophy and an inability to stay attached to the substratum.

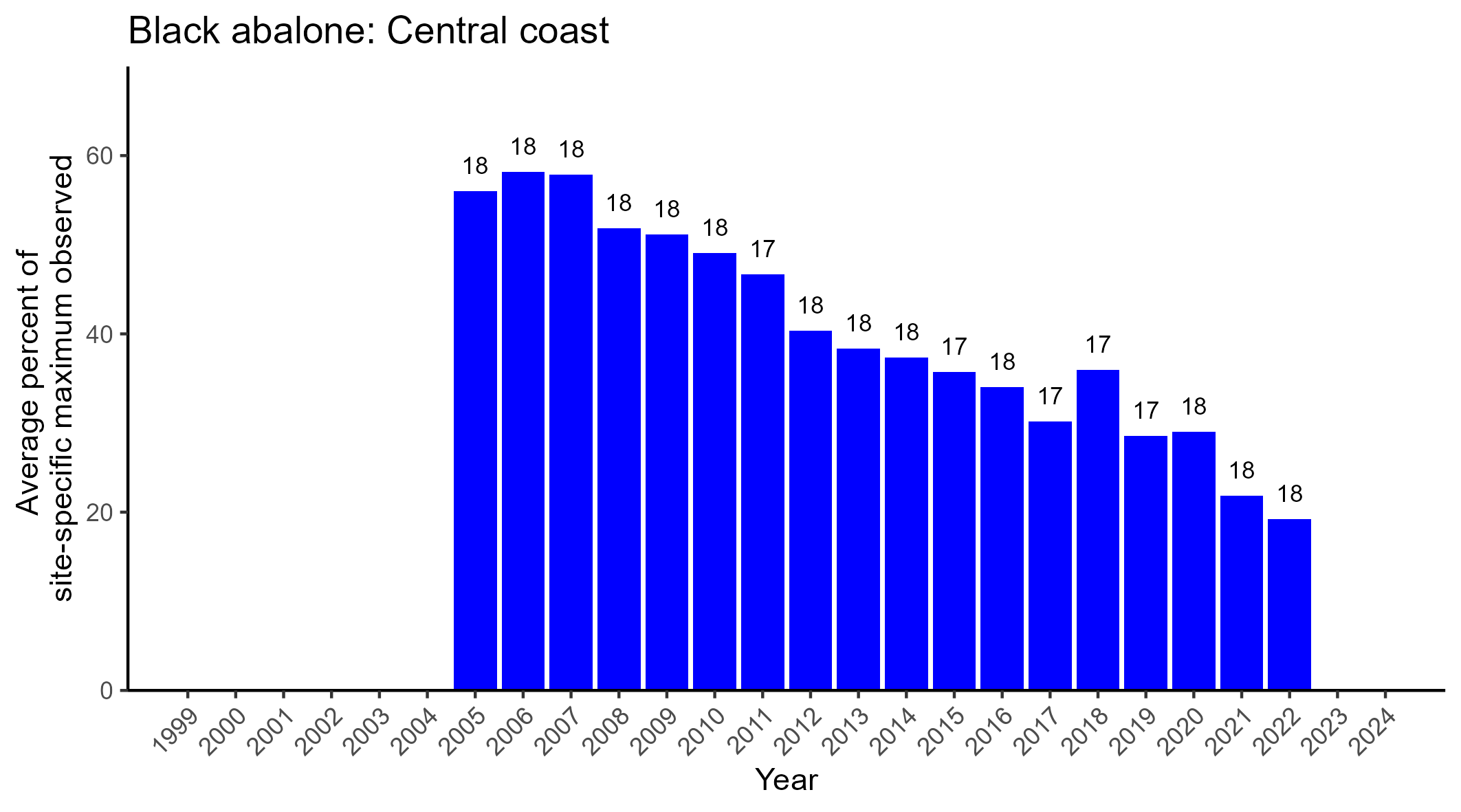

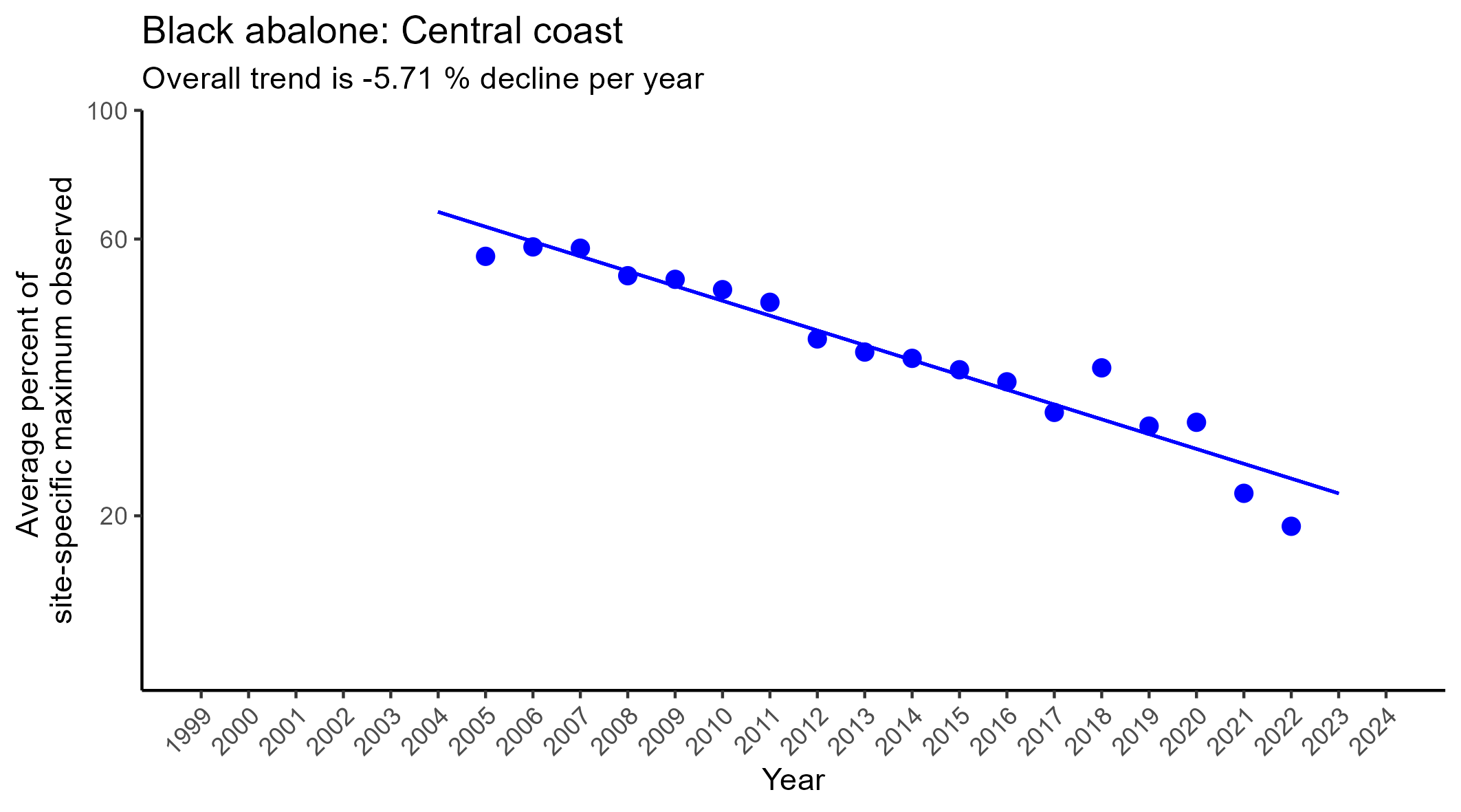

Data from 1999 to the present demonstrate a continued strong decreasing trend in the species, averaging an annual decline of 5.71%, which as a linear trend explains 93% of the year-to-year variation in black abalone counts. Although harvest of black abalone is now prohibited due to its listing as an endangered species, its population is not recovering. Chronic factors underlying the slow or non-existent recovery of black abalone include the persistence of WS, illegal poaching, sediment burial, and habitat loss. Three distinct phenomena have exacerbated the recent decline of black abalone: 1) landslides, particularly along the Big Sur coast, 2) wildfire followed by flooding incidents that result in unusually high deposition of sediment and debris into intertidal habitat, and 3) expansion of mussel beds into crevices formerly occupied by abalone, which is likely an indirect result of sea star loss from disease.

The situation for black abalone is not without hope. Scientists have discovered a bacteriophage that infects the WS pathogen and reduces its lethality. At the same time genetic analyses may help identify genes for resistance to WS. Researchers at the University of California, Santa Cruz (UCSC) have led emergency response efforts, successfully rescuing and relocating black abalone at risk of sediment burial. Active restoration is also underway, including translocation efforts to increase black abalone abundance and density in areas where they have experienced declines. In addition, NOAA researchers at the Southwest Fisheries Science Center have successfully induced spawning in black abalone using synthetic mollusk hormones. The basis for all of this work is continued long-term monitoring to assess black abalone trends over time. There will likely be an opportunity for the Aquarium of the Pacific and other facilities to contribute to black abalone restoration, including translocation, rescue and relocation, aquaculture and re-release into the wild, and long-term monitoring.

Population Plots

Data Source: The data were obtained from the Multi-Agency Rocky Intertidal Network (MARINe) for rocky intertidal sampling locations that are part of the MARINe network (see https://marine.ucsc.edu/). The MARINe website describes the sampling protocol. Data are shown only for the Central Coast because that is the region with the vast majority of sample sites, and hence the most reliable source of data for trends.