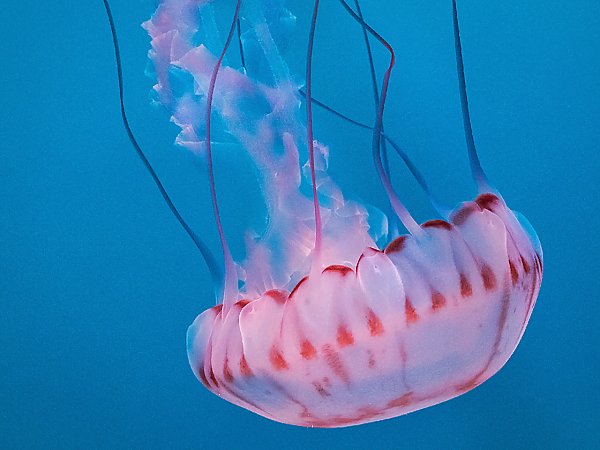

Purple-striped Jelly

Chrysaora colorata

The bell of a purple-striped jelly has been described as resembling a Tiffany lamp shade. While juveniles lack purple stripes, adult purple-striped jellies are appropriately named. These jellies that are primarily found in California waters are usually open-ocean dwellers, although SCUBA divers observe them from time to time close to the offshore Huntington Beach, California, oil platforms.

Credit: Robin Riggs

SPECIES IN DETAIL

Purple-striped Jelly

Chrysaora colorata

CONSERVATION STATUS: Safe for Now

CLIMATE CHANGE: Uncertain

At the Aquarium

The purple-striped jellies’ Aquarium habitat is in the Southern California/Baja gallery. The jellies were propagated by our aquarists. The number of jellies produced has been large enough that cultured purple-striped jellies could be shared with other aquariums.

Geographic Distribution

Pacific Ocean, primarily off the coast of California including Monterey and Bodega Bays, off Santa Barbara, and in the San Pedro Basin.

Habitat

The purple-striped jelly’s habitat is believed to be open ocean water and perhaps waters overlying the continental shelf.

Physical Characteristics

The bell of the purple-striped jelly is bowl-shaped. Four long, frilly oral arms that appear to be coiled and spiraled hang below the bell margin. The arms may be lacking in older jellies. Eight thin, long tentacles also hang from the bell’s margin. These alternate with eight sensory rhopalia that have 16 lappets.

The exumbrella of the bell of large jellies is a pale silvery white color. There is a deep purple pattered ring at the top of the bell and 16 radial streaks or stripes with dark colored lappets. The oral arms are pinkish in color. Juveniles have a pale pinkish colored bell and dark reddish tentacles. They do not have the purple radial streaks.

Size

Bell diameter to 70 centimeters (28 inches) Tentacles extended to 21 meters (70 feet) Oral arms to 30 centimeters (12 inches)

Diet

This jelly is an opportunistic predator. Its diet includes copepods, larval fishes, planktonic crustaceans, fish eggs, pelagic tunicates, ctenophores (comb jellies), and and other medusa jellies.

Reproduction

It was not until about 2008, with observation of polyps, that scientists were able to determine that purple-striped jellies had a two-phase reproductive cycle, sexual and asexual.

The sexual stage: Adult medusae are either male or female. The male medusa releases mucus strands of sperm from the tips of its oral arms that are picked up by the female’s tentacles and oral arms. As the strands break up, the female transfers the sperm to her gastrovascular cavity where fertilization occurs. Fertilized eggs are moved outward to the innermost edges of the female’s oral arms where they are brooded and develop into ciliated larvae.

From ciliated free-swimming larvae to sessile polyps: The larvae eventually break off and become planulae; they beat their cilia to swim, searching for a suitable hard, rough, and shaded substrate such as a rock or piling, to attach to. The planulae then attach upside-down and become planocysts.

The asexual stage: Sessile planocysts morph into polyps (scyphistomes) that grow tentacles with which to filter feed. Depending on environmental conditions (water temperature, salinity, and nutrients), one of two asexual processes takes place. If conditions are unfavorable, a scyphistoma buds off tissue fragments that form a genetically identical clone of itself. Such budding may persist for months or even several years until conditions are ideal for the other form of asexual reproduction—strobilation—to take place.

In strobilation, structures called strobilia are formed on a stalk, one on top of the other like a stack of dinner plates with the most mature on top. The strobilia bud off as individual eyphyra that are 3 mm (0.125 inches) in diameter and look like flattened flower petals.

Developing into medusa: During the next two to three months, in order, the eyphrae develop marginal lobes, rhopalia, tentacles, elaborate oral arms, and finally the bell shape of the adult medusa, the form in which sexual reproduction occurs.

Behavior

As the purple-striped jelly swims, its long tentacles trail behind. When the highly contractile tentacles touch prey, nematocysts are immediately discharged and the tentacles contract. As the stiff tentacle bends toward the nearest oral arm, the arm moves inward, turns slightly, and draws its inner layer near the prey. The tentacle then releases the prey, which the oral arm grasps and starts a muscle contraction that drives the prey into the oral arm groove, then to the mandribium, and finally the gastric cavity. The oral arms also collect prey directly without use of the tentacles.

This jelly has a symbiotic relationship with juvenile slender crabs (Cancer gracilis) that travel with the jelly host in open waters among its tentacles until the crabs are ready to become bottom dwellers. How the crabs protect themselves from the nematocysts’ stings is not known. It may be that the shell offers protection.

Adaptation

This jelly’s sting is very painful, but not life threatening.

The purple-striped jelly has both radial and coronal muscles. In the swimming stroke the coronal muscles act first drawing the umbrella inward and downward. The radial muscles then cause a further flexion of the umbrella. There is an initial backward thrust of the umbrella on the water. An outward jet of water is produced with each contraction. There is sufficient drag on the bell to virtually stop the jelly in the water at the end of recovery. The animal must then accelerate again during the next beat.

This jelly reacts to increased light by decreasing its pulsations. It has the ability to perceive the ocean bottom and surface, avoiding both in its normal behavior. Balance is maintained through the statocysts, the balance and orientation organs. The sensory lappets enable the jelly to react to touch. The nerve tissue associated with the rhopalia triggers the contraction of the swimming bell.

Longevity

These relatively fragile, easily damaged jellies probably live about a year or less, if that long.

Conservation

Because they do not swarm and wash up on the beach in large numbers, purple-striped jellies are not the same problem to beachgoers and boaters as are some of their sea nettle relatives are.

Special Notes

The genus of purple-striped jellies was originally Pelagia until taxonomists changed it to Chrysaora, the genus of sea nettles. The change was made primarily because of morphological similarities to sea nettles; in fact, the purple-striped jelly is sometimes called the purple-striped sea nettle.

SPECIES IN DETAIL | Print full entry

Purple-striped Jelly

Chrysaora colorata

CONSERVATION STATUS: Safe for Now

CLIMATE CHANGE: Uncertain

The purple-striped jellies’ Aquarium habitat is in the Southern California/Baja gallery. The jellies were propagated by our aquarists. The number of jellies produced has been large enough that cultured purple-striped jellies could be shared with other aquariums.

Pacific Ocean, primarily off the coast of California including Monterey and Bodega Bays, off Santa Barbara, and in the San Pedro Basin.

The purple-striped jelly’s habitat is believed to be open ocean water and perhaps waters overlying the continental shelf.

The bell of the purple-striped jelly is bowl-shaped. Four long, frilly oral arms that appear to be coiled and spiraled hang below the bell margin. The arms may be lacking in older jellies. Eight thin, long tentacles also hang from the bell’s margin. These alternate with eight sensory rhopalia that have 16 lappets.

The exumbrella of the bell of large jellies is a pale silvery white color. There is a deep purple pattered ring at the top of the bell and 16 radial streaks or stripes with dark colored lappets. The oral arms are pinkish in color. Juveniles have a pale pinkish colored bell and dark reddish tentacles. They do not have the purple radial streaks.

Bell diameter to 70 centimeters (28 inches) Tentacles extended to 21 meters (70 feet) Oral arms to 30 centimeters (12 inches)

This jelly is an opportunistic predator. Its diet includes copepods, larval fishes, planktonic crustaceans, fish eggs, pelagic tunicates, ctenophores (comb jellies), and and other medusa jellies.

It was not until about 2008, with observation of polyps, that scientists were able to determine that purple-striped jellies had a two-phase reproductive cycle, sexual and asexual.

The sexual stage: Adult medusae are either male or female. The male medusa releases mucus strands of sperm from the tips of its oral arms that are picked up by the female’s tentacles and oral arms. As the strands break up, the female transfers the sperm to her gastrovascular cavity where fertilization occurs. Fertilized eggs are moved outward to the innermost edges of the female’s oral arms where they are brooded and develop into ciliated larvae.

From ciliated free-swimming larvae to sessile polyps: The larvae eventually break off and become planulae; they beat their cilia to swim, searching for a suitable hard, rough, and shaded substrate such as a rock or piling, to attach to. The planulae then attach upside-down and become planocysts.

The asexual stage: Sessile planocysts morph into polyps (scyphistomes) that grow tentacles with which to filter feed. Depending on environmental conditions (water temperature, salinity, and nutrients), one of two asexual processes takes place. If conditions are unfavorable, a scyphistoma buds off tissue fragments that form a genetically identical clone of itself. Such budding may persist for months or even several years until conditions are ideal for the other form of asexual reproduction—strobilation—to take place.

In strobilation, structures called strobilia are formed on a stalk, one on top of the other like a stack of dinner plates with the most mature on top. The strobilia bud off as individual eyphyra that are 3 mm (0.125 inches) in diameter and look like flattened flower petals.

Developing into medusa: During the next two to three months, in order, the eyphrae develop marginal lobes, rhopalia, tentacles, elaborate oral arms, and finally the bell shape of the adult medusa, the form in which sexual reproduction occurs.

As the purple-striped jelly swims, its long tentacles trail behind. When the highly contractile tentacles touch prey, nematocysts are immediately discharged and the tentacles contract. As the stiff tentacle bends toward the nearest oral arm, the arm moves inward, turns slightly, and draws its inner layer near the prey. The tentacle then releases the prey, which the oral arm grasps and starts a muscle contraction that drives the prey into the oral arm groove, then to the mandribium, and finally the gastric cavity. The oral arms also collect prey directly without use of the tentacles.

This jelly has a symbiotic relationship with juvenile slender crabs (Cancer gracilis) that travel with the jelly host in open waters among its tentacles until the crabs are ready to become bottom dwellers. How the crabs protect themselves from the nematocysts’ stings is not known. It may be that the shell offers protection.

This jelly’s sting is very painful, but not life threatening.

The purple-striped jelly has both radial and coronal muscles. In the swimming stroke the coronal muscles act first drawing the umbrella inward and downward. The radial muscles then cause a further flexion of the umbrella. There is an initial backward thrust of the umbrella on the water. An outward jet of water is produced with each contraction. There is sufficient drag on the bell to virtually stop the jelly in the water at the end of recovery. The animal must then accelerate again during the next beat.

This jelly reacts to increased light by decreasing its pulsations. It has the ability to perceive the ocean bottom and surface, avoiding both in its normal behavior. Balance is maintained through the statocysts, the balance and orientation organs. The sensory lappets enable the jelly to react to touch. The nerve tissue associated with the rhopalia triggers the contraction of the swimming bell.

These relatively fragile, easily damaged jellies probably live about a year or less, if that long.

Because they do not swarm and wash up on the beach in large numbers, purple-striped jellies are not the same problem to beachgoers and boaters as are some of their sea nettle relatives are.

The genus of purple-striped jellies was originally Pelagia until taxonomists changed it to Chrysaora, the genus of sea nettles. The change was made primarily because of morphological similarities to sea nettles; in fact, the purple-striped jelly is sometimes called the purple-striped sea nettle.