Greater Blue-ringed Octopus

Hapalochlaena lunulata

The greater blue-ringed octopus is one of several species of blue-ringed octopuses. All are thought to be venomous and for their size, they are the most deadly of all cephalopods. It is said that the venom of this octopus could kill 26 adults in just a few minutes. There is no antivenin for treatment. Fortunately, these octopuses do not attack humans. Injury typically occurs when a blue-ringed octopus is stepped on or picked up.

Credit: R.Caldwell. Used with permission

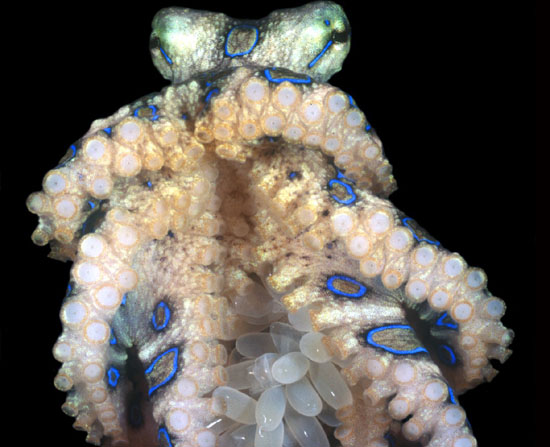

Octopus with eggs Credit: R.Caldwell. Used with permission

SPECIES IN DETAIL

Greater Blue-ringed Octopus

Hapalochlaena lunulata

CONSERVATION STATUS: Safe for Now

CLIMATE CHANGE: Not Applicable

At the Aquarium

Not on exhibit. Information included in the Ocean Learning Center for use as a reference. Our thanks to Dr. Roy Caldwell, University of California Berkeley, for his review of this information.

Geographic Distribution

Northern Australia to Japan including Papua New Guinea, Solomon Islands, and Indonesia as far west as Sri Lanka.

Habitat

These octopus are bottom dwellers inhabiting sandy and silty areas in shallow coral reefs, tidepools, and clumps of algae at depths of 0-20 m (0-66 ft).They hide in rock crevices, inside empty seashells, and in discarded bottles and cans.

Physical Characteristics

Greater blue-ringed octopuses have a soft sac-like body and eight sucker-covered arms. Their body background color at rest is usually tan to dark yellow. or occasionally gray. Up to 25 faint blue rings as large as 8 mm (0.3 in) in diameter cover the dorsal surface, mantle, and extend out over the arms. The center of each ring is usually a dark brown color. Each ring has a dark blurred edge, containing some of the chromatophores that cause color changes when the animal is stressed. At such a time the, faint blue rings change to a brilliant iridescent blue that often seem to glow. A short blue line runs through the eyes. The body is often covered with papillae that give it a rough appearance.

Size

The body of H. lunulata is about the size of a grape seed at birth and that of a golf ball at maturity. Adults are usually less than 5 cm (1.97 in) long with arms to 7 cm (2.8 in) when extended. They weigh 10 to 100 g, avg. 55 g (0.35-3.5 oz, avg. 1.9 oz). Females are slightly larger than males.

Diet

Blue-ringed-octopuses hunt during the day. They eat small crabs, hermit crabs, shrimp, and occasionally small fishes: however, they are primarily crab-eaters. Ambush predators, they usually pounce on their hard-shelled prey trap it with their arms and use their sharp parrot-like beak to pierce a hole in the prey’s shell or exoskeleton. Venomous saliva is then dribbled into the wound. (Envenomization differs from that used by rattlesnakes which inject their toxic saliva.) When the prey is paralyzed, the predatory octopus uses its beak to tear off and eat the softer parts of the animal. Enzymes in its saliva partially digests the remaining flesh which the octopus sucks out, leaving the shell behind. Reports that this species sprays venom into the surrounding water to paralyze prey are still under investigation.

Reproduction

These octopus begin to reproduce when they are less than a year old. Sexes are separate. An interested male typically pounces on a female (and often other males) and tries to insert his hectocotylus into the female’s mantle cavity while holding onto her mantle. During the initial pounce by the male, the female may display her bright blue rings. If the male succeeds, he releases spermatophores into her mantle cavity. Shortly after mating, the female lays 50 to 100 eggs. Studies have shown that the eggs contain venom. The female broods the eggs under her mantle in a cluster on her arms for about 30 days. She usually does not eat during the brooding period. The eggs hatch into 4 mm (0.16) long planktonic “paralarva”. The larvae swim freely in the ocean for about a month gaining weight. They then settle to the ocean floor where they live out their life span. The female dies shortly after the eggs hatch.

Behavior

Blue-ringed octopuses are not aggressive. They usually remain in crevices among rocks, inside shells, and even in discarded bottles and cans. They emerge only to hunt food or look for a mate.

Adaptation

As blue-ringed octopus evolved, they partially lost their defensive ability to ink as their ink sac became smaller and smaller. Today’s juveniles can still ink but the ink sac greatly reduces in size as the octopus grows.

Blue-ringed octopus have very toxic venom, tetrodotoxin, that is produced in two posterior salivary glands by symbiotic bacteria. This venom is more toxic than of any land animal. Research studies are being done in an effort to learn how the bacteria are acquired and whether blue-ringed octopuses lose their toxin producing capability when removed from the wild to a protected environment such as an aquarium. It has been confirmed that blue-ringed octopuses are immune to the venom of their own and that of other pygmy octopus.

Longevity

Not a great deal is known about how long these octopuses live, but they are believed to have a life span of about a year.

Conservation

Blue-ringed octopuses are not listed on the IUCN Red List nor are they protected.

Special Notes

Blue-ringed octopuses get their common name from their blue rings. The ‘greater’ part of the common name of H. lunulata comes not from its body size, but from the size of the blue rings on its dorsal surface and arms.

The blue-ringed octopus has been featured in several films and TV shows; the James Bond movie, Octopussy, where the tattoo of the octopus indicted a secret order of male bandits and smugglers; the TV movie, Profiles; and in the novel State of Fear.

SPECIES IN DETAIL | Print full entry

Greater Blue-ringed Octopus

Hapalochlaena lunulata

CONSERVATION STATUS: Safe for Now

CLIMATE CHANGE: Not Applicable

Not on exhibit. Information included in the Ocean Learning Center for use as a reference. Our thanks to Dr. Roy Caldwell, University of California Berkeley, for his review of this information.

Northern Australia to Japan including Papua New Guinea, Solomon Islands, and Indonesia as far west as Sri Lanka.

These octopus are bottom dwellers inhabiting sandy and silty areas in shallow coral reefs, tidepools, and clumps of algae at depths of 0-20 m (0-66 ft).They hide in rock crevices, inside empty seashells, and in discarded bottles and cans.

Greater blue-ringed octopuses have a soft sac-like body and eight sucker-covered arms. Their body background color at rest is usually tan to dark yellow. or occasionally gray. Up to 25 faint blue rings as large as 8 mm (0.3 in) in diameter cover the dorsal surface, mantle, and extend out over the arms. The center of each ring is usually a dark brown color. Each ring has a dark blurred edge, containing some of the chromatophores that cause color changes when the animal is stressed. At such a time the, faint blue rings change to a brilliant iridescent blue that often seem to glow. A short blue line runs through the eyes. The body is often covered with papillae that give it a rough appearance.

The body of H. lunulata is about the size of a grape seed at birth and that of a golf ball at maturity. Adults are usually less than 5 cm (1.97 in) long with arms to 7 cm (2.8 in) when extended. They weigh 10 to 100 g, avg. 55 g (0.35-3.5 oz, avg. 1.9 oz). Females are slightly larger than males.

Blue-ringed-octopuses hunt during the day. They eat small crabs, hermit crabs, shrimp, and occasionally small fishes: however, they are primarily crab-eaters. Ambush predators, they usually pounce on their hard-shelled prey trap it with their arms and use their sharp parrot-like beak to pierce a hole in the prey’s shell or exoskeleton. Venomous saliva is then dribbled into the wound. (Envenomization differs from that used by rattlesnakes which inject their toxic saliva.) When the prey is paralyzed, the predatory octopus uses its beak to tear off and eat the softer parts of the animal. Enzymes in its saliva partially digests the remaining flesh which the octopus sucks out, leaving the shell behind. Reports that this species sprays venom into the surrounding water to paralyze prey are still under investigation.

These octopus begin to reproduce when they are less than a year old. Sexes are separate. An interested male typically pounces on a female (and often other males) and tries to insert his hectocotylus into the female’s mantle cavity while holding onto her mantle. During the initial pounce by the male, the female may display her bright blue rings. If the male succeeds, he releases spermatophores into her mantle cavity. Shortly after mating, the female lays 50 to 100 eggs. Studies have shown that the eggs contain venom. The female broods the eggs under her mantle in a cluster on her arms for about 30 days. She usually does not eat during the brooding period. The eggs hatch into 4 mm (0.16) long planktonic “paralarva”. The larvae swim freely in the ocean for about a month gaining weight. They then settle to the ocean floor where they live out their life span. The female dies shortly after the eggs hatch.

Blue-ringed octopuses are not aggressive. They usually remain in crevices among rocks, inside shells, and even in discarded bottles and cans. They emerge only to hunt food or look for a mate.

As blue-ringed octopus evolved, they partially lost their defensive ability to ink as their ink sac became smaller and smaller. Today’s juveniles can still ink but the ink sac greatly reduces in size as the octopus grows.

Blue-ringed octopus have very toxic venom, tetrodotoxin, that is produced in two posterior salivary glands by symbiotic bacteria. This venom is more toxic than of any land animal. Research studies are being done in an effort to learn how the bacteria are acquired and whether blue-ringed octopuses lose their toxin producing capability when removed from the wild to a protected environment such as an aquarium. It has been confirmed that blue-ringed octopuses are immune to the venom of their own and that of other pygmy octopus.

Not a great deal is known about how long these octopuses live, but they are believed to have a life span of about a year.

Blue-ringed octopuses are not listed on the IUCN Red List nor are they protected.

Blue-ringed octopuses get their common name from their blue rings. The ‘greater’ part of the common name of H. lunulata comes not from its body size, but from the size of the blue rings on its dorsal surface and arms.

The blue-ringed octopus has been featured in several films and TV shows; the James Bond movie, Octopussy, where the tattoo of the octopus indicted a secret order of male bandits and smugglers; the TV movie, Profiles; and in the novel State of Fear.