Aquarium Discounts

Aquarium coupons at Baker’s through December

The Aquarium of the Pacific is part of a conservation network committed to recovering the population of white abalone by breeding them and releasing young abalone into the ocean.

Credit: Jen Burney

Hidden among the rocks of a kelp forest are marine snails called abalone. Known as ecosystem architects, these unassuming animals graze on seaweed creating open space for many types of seaweed to grow, which promotes a diverse habitat full of fish and other animals. White abalone (Haliotis sorenseni) were once so abundant that they were collected as food and their shells were used as tools and for jewelry. Unfortunately, commercial fishing in the 1970s decimated the population. White abalone have been protected from fishing since 1997, and in 2001, they were the first marine invertebrate to gain protection under the Endangered Species Act. Even with those efforts, their population continues to decline, and they need our help.

White abalone reproduce by spawning, which means they release their tiny eggs and sperm into ocean waters where they drift until they meet and the egg is fertilized. Currently, there are not enough white abalone in the ocean for the tiny eggs and sperm to meet causing their population to decline. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) recognized the need to step in to create a captive breeding and release program. It all started as a collection of 20 abalone from the wild and turned into a partnership of scientists and educators from over a dozen government agencies, universities, and aquariums.

As a founding partner of the White Abalone Recovery Program, the Aquarium of the Pacific collaborates with NOAA, the UC Davis Bodega Marine Laboratory, the Bay Foundation, Paua Marine Research Group, the California Department of Fish and Wildlife, and various other organizations to breed and raise abalone.

The first step is encouraging the adult white abalone to spawn, and hopefully, at least one female and one male do. They only spawn once a year, so this is a difficult and important process. If it is successful, the tiny eggs and sperm are mixed together, and the microscopic baby white abalone float in flowing seawater until they grow large enough to settle on small plates that are encrusted with their favorite food… algae! They are still too small to see without a microscope, but dots appear as they graze, cleaning tiny areas of algae off the plates. Wait just a bit longer and the baby abalone are finally big enough to see!

We continue to raise them until they are around 25 mm long and ready for release. Each abalone is tagged with a color and individual number so they can be identified if they are found after release. Once it is time, the young white abalone are introduced to sites identified by scientific divers from the Aquarium and partner organizations. This introduction takes place in algae-filled protective boxes called SAFEs (short-term abalone fixed enclosures) to ensure the young white abalone are protected from predators while they acclimate to their new kelp forest home. Once they are released from the SAFEs, divers will occasionally visit release sites to monitor the area and make note of evidence of living abalone or abalone shells.

Starting in 2019, thousands of young abalone have been released at several sites off the coast of Southern California. The hope is that with continued work, white abalone will reach sustainable populations again and this project will no longer be needed.

Until then, we can all help the white abalone by supporting a clean and diverse ocean. In addition, the Aquarium of the Pacific is partnering with the NOAA Channel Islands National Marine Sanctuary and NOAA Fisheries Office of Protected Resources to promote Finding Hal, a campaign to encourage recreational divers to report sightings of white abalone. Identification cards and other resources are provided so the diving community can help white abalone conservation efforts.

Credit: Oriana Poindexter

White abalone are endangered marine snails found along the coast of Southern California and Baja, Mexico.

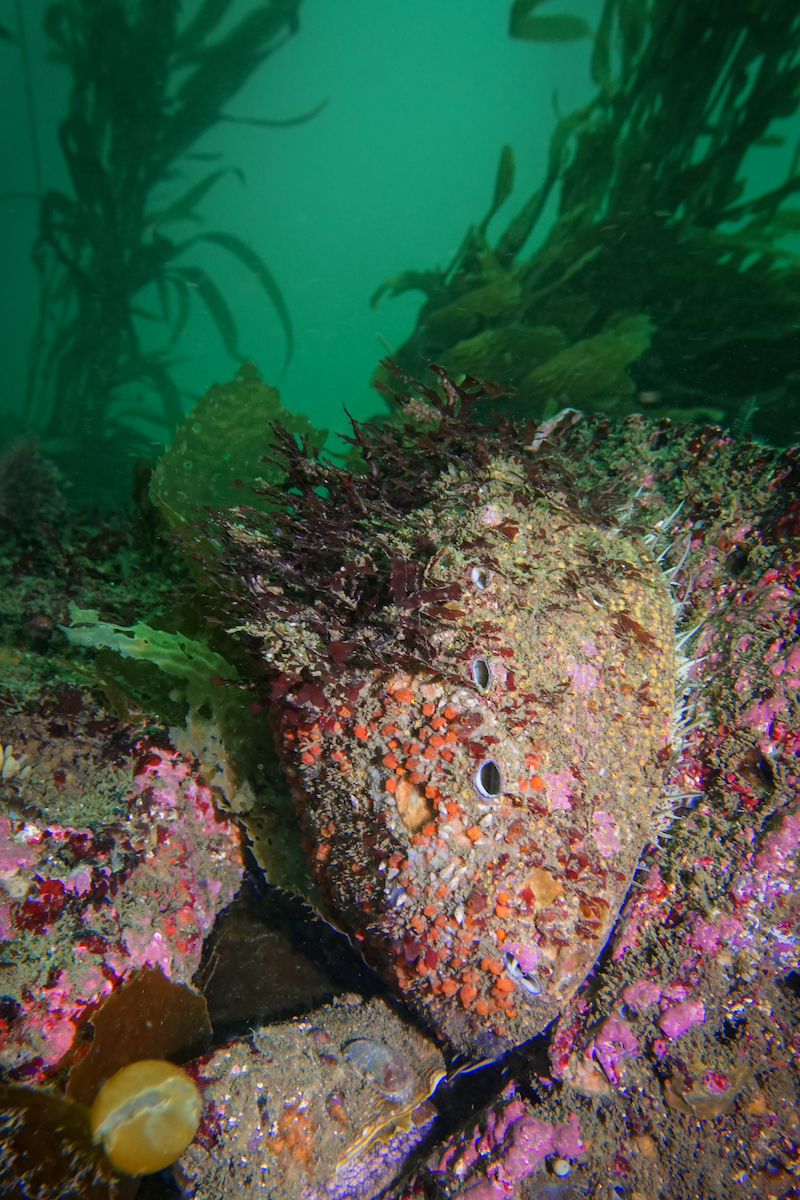

Credit: Oriana Poindexter

White abalone are covered with other marine life giving them camouflage in their kelp forest habitat.

Credit: Aquarium of the Pacific

Adult abalone are separated into buckets to collect their eggs or sperm when they spawn.

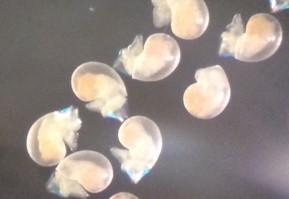

Credit: Aquarium of the Pacific

Larval abalone are microscopic and float around in water until they grow large enough to settle.

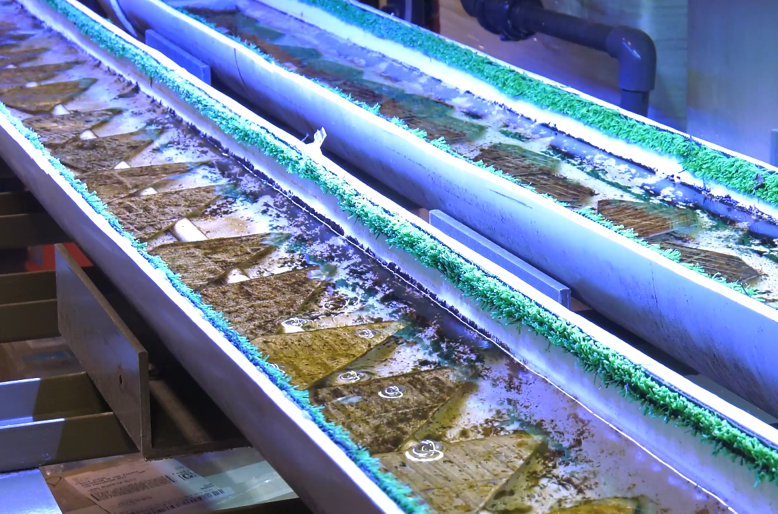

Credit: Aquarium of the Pacific

When it’s time for larval abalone to settle, they are introduced to these algae covered plates for easy access to food.

Credit: Oriana Poindexter

We raise the young abalone until they are large enough for outplanting.

Credit: Aquarium of the Pacific / Andrew Reitsma

Before release, the young abalone are numbered with colored tags allowing us to keep track of them after outplanting.

Credit: Oriana Poindexter

Young white abalone are released in protective enclosures to acclimate before venturing into their new home.

Aquarium coupons at Baker’s through December